Weekly Top Five Articles

Screens Before Age 2 Causes Brain Damage & Teen Anxiety, Free-Choice Marries & Arranged Marriages Don't Different in Romantic Passion, and more. . .

Here’s what stood out this week. . .

(1) “Inside the Long History of Technologically Assisted Writing,” by Ed Simon, Literary Hub, January 21, 2026

Ed Simon on the Eternal Tension Between Human Creativity and Mechanical Efficiency

Well, y’all, it seems that mechanical writing (like AI) isn’t new and something we’re attempted to perfect for some time. Simon situates contemporary anxiety about AI writing within a millennium-long history of mechanically assisted creativity, arguing that ChatGPT-3 revives, rather than invents, fears about machines supplanting human authorship. Responding to early alarms by Stephen Marche, Simon grants the real power of generative language models, especially their speed and plausibility, while insisting that the deeper threat is not technological but economic and cultural: who controls these tools, and to what ends.

Tracing a lineage from oracles and the classical deus ex machina through Jonathan Swift’s satirical Engine in Gulliver’s Travels, Simon shows that algorithmic writing long predates silicon. Medieval combinatorial systems such as Ramon Llull’s Ars Magna, playful constraints like Mad Libs and Oulipo, and nineteenth-century marvels such as John Clark’s Eureka machine all demonstrate that formula, chance, and creativity have always coexisted. These devices produced prose that was often mediocre, sometimes eerie, and occasionally profound, forcing uncomfortable questions about meaning, consciousness, and intention.

Twentieth-century computing intensified the pattern. Alan Turing and Christopher Strachey’s machine-generated love letters, later programs like Racter, and today’s ChatGPT reveal not cold rationality but a strange, almost oracular mimicry of human longing. For Simon, this resemblance unsettles because it exposes how much writing already depends on structure, repetition, and laborious revision rather than pure inspiration.

Yet Simon’s central claim is ethical and political. Technologies are neutral; systems of production are not. Like the Luddites before them, writers face dispossession less by machines than by owners who deploy automation to extract profit while preserving drudgery for everyone else. The utopian promise that machines would free humans for creative life has inverted itself.

Simon concludes with a humanism. AI may generate text, but it cannot read, remember, or suffer. Meaning still arises in interpretive communities, through human attention. Creation, he insists, is a process, not a product. Maybe AI isn’t the villain that many say that it is.

(2) “Is inherited wealth bad?,” by Daniel Waldenström, Aeon, (January 29, 2026)

If anyone has wealth that they don’t want to give to their family members, I’ll happily take it off your hands. Waldenström challenges the rising alarm that Western societies are sliding into an age of inheritocracy. While inheritance flows have indeed increased as a share of national income, he argues that this trend reflects demographic aging, rising wealth stocks, and slower income growth rather than a revival of feudal capitalism. Headlines warning of a ‘great wealth transfer’ obscure a more complex reality: modern economies remain far more dynamic and merit-based than their early twentieth-century predecessors.

Drawing on long-run data from Europe, the United States, and Asia, Waldenström shows that inherited wealth plays a smaller structural role today than a century ago. Although roughly 10 percent of national income is transferred annually through bequests in rich countries, the share of total wealth that is inherited has fallen sharply. Where inheritance once accounted for as much as 80 percent of private wealth, it now represents closer to half, with most wealth accumulated within a single lifetime through work, saving, and entrepreneurship.

The distributional effects of inheritance further complicate moral intuitions. While wealthy heirs receive larger bequests in absolute terms, those transfers typically add little to already substantial fortunes. For middle- and lower-wealth heirs, modest inheritances can be transformative, often doubling or tripling net worth. Empirical evidence suggests that among recipients, inheritance slightly compresses wealth inequality, even as it reinforces inequality of opportunity across families.

Waldenström is especially skeptical of inheritance taxation. Estate taxes raise little revenue, distort investment decisions, and are riddled with exemptions that blunt their egalitarian aims. Many countries, including Sweden, have abandoned them in favor of more effective capital income taxes. The real path to fairness, he contends, lies not in punishing bequests but in expanding access to wealth creation through education, entrepreneurship, and broad asset ownership. Growth, not confiscation, remains the durable engine of equality in advanced capitalist societies today.

I, for one, would love to estate taxes abolished.

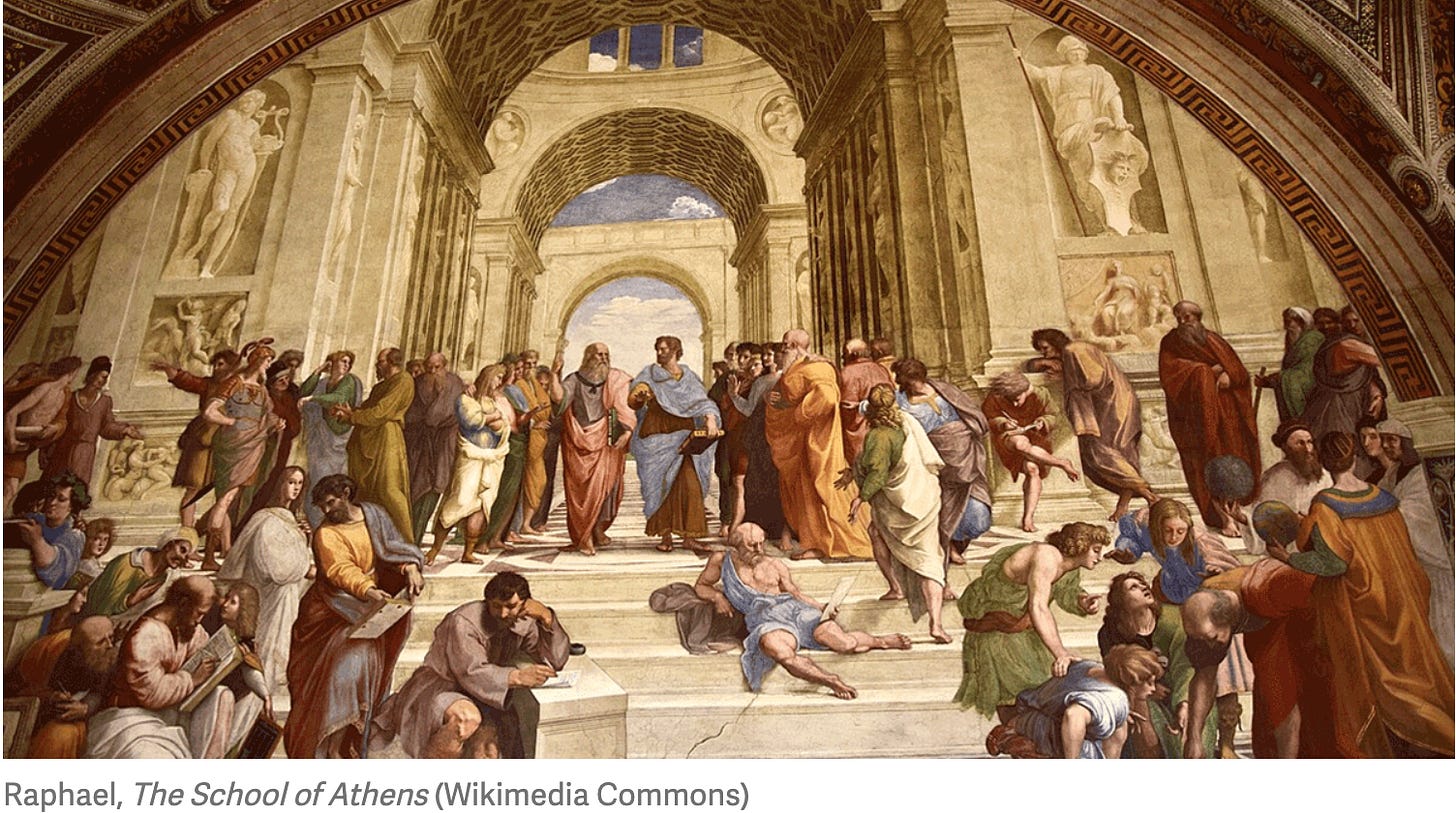

(3) “The Popper Principle: Did Plato really espouse ideas that led eventually to totalitarianism?,” By Robert Zaretsky, (January 29, 2026)

Zaretsky revisits Karl Popper’s most provocative claim: that Plato, the architect of Western philosophy, supplied conceptual foundations later exploited by totalitarian regimes. This is a fascinating perspective. I was first introduced to Popper at Clemson when I took a philosophy of science class.

Writing in the shadow of fascism and exile, Popper extended his scientific principle of fallibilism into politics, arguing that open societies advance through criticism, revision, and dialogue, while closed societies seek to freeze history itself.

In The Open Society and Its Enemies, Popper read Plato’s Republic not as a timeless meditation on justice but as a blueprint for authoritarian order. Plato’s ideal city, rigidly stratified and governed by philosopher-kings, relies on “noble lies” to legitimate hierarchy and suppress dissent. Myth replaces criticism, poets are exiled, and citizens are trained to accept their assigned place as natural. For Popper, this desire to arrest change marks the psychological core of totalitarianism, ancient or modern.

Zaretsky situates Popper’s reading within its historical urgency. A Jewish intellectual fleeing interwar Vienna, Popper wrote as Europe descended into genocide, later learning that much of his own family had perished. His interpretation of Plato was thus sharpened by catastrophe, emotionally charged yet morally serious. Though critics accuse Popper of caricature, Zaretsky suggests his alarm was not misplaced. Plato’s suspicion of democracy, reverence for guardianship, and willingness to subordinate truth to stability resonate uncomfortably with twentieth-century ideologies built on pseudoscience and myth.

Yet Zaretsky resists reducing Plato to a villain. Plato’s dialogues, unlike manifestos, invite questioning rather than obedience, and Socrates embodies the examined life Popper himself prized. The irony is that modern censors who suppress classical texts in the name of order replicate precisely the closed society Popper warned against.

The essay ultimately affirms Popper’s enduring insight: history has no predetermined meaning, yet responsibility remains. An open society survives only through dialogue, humility before error, and the courage to live with freedom together today.

(4) “Researchers identify the psychological mechanisms behind the therapeutic effects of exercise,” by Eric W. Dolan, PsyPost (January 29, 2026)

Dolan reports on a study that sharpens a long-standing intuition about exercise and mental health into something closer to a causal account. Physical activity, the research suggests, does not merely lift mood in some vague, biochemical way. It works by reshaping how people experience stress and how tightly they cling to destructive patterns of thought.

Drawing on a large randomized controlled trial conducted in Germany, the study followed nearly 400 physically inactive adults diagnosed with conditions such as depression, panic disorder, PTSD, or insomnia. Participants assigned to a six-month, structured running program showed significantly greater reductions in overall psychiatric symptoms than those receiving standard treatment alone. Crucially, these improvements persisted a year later.

What distinguishes this analysis is its focus on mechanisms. The authors tested whether exercise worked by improving sleep, reducing perceived stress, or interrupting repetitive negative thinking. The answer was unambiguous. Symptom reduction was fully explained by declines in stress perception and rumination. Sleep quality, often assumed to be central, played no mediating role. Exercise helped not because participants slept better, but because they felt less overwhelmed by life and less trapped inside their own intrusive thoughts.

The findings align with two influential theories. The “cross-stressor adaptation” hypothesis suggests that repeated physical stress trains the body and mind to respond more calmly to psychological stress. The “distraction” hypothesis explains how focused physical effort can break cycles of rumination that sustain depression and anxiety.

As Anna Katharina Frei notes, these mechanisms cut across diagnoses, making exercise a rare transdiagnostic intervention. The implication is quietly radical. Exercise is not merely an adjunct or lifestyle recommendation, but a cognitive intervention that teaches people, through their bodies, how not to be governed by stress and thought loops that quietly erode mental health.

(5) “Common air pollutants associated with structural changes in the teenage brain,”by Eric W. Dolan, PsyPost (January 26, 2026)

Eric W. Dolan reports on research that quietly unsettles the assumption that adolescent brain development unfolds largely independent of ordinary environmental conditions. Drawing on nearly 11,000 participants from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, researchers find that routine exposure to common air pollutants is associated with measurable changes in how the teenage brain matures over time.

The study focuses on fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide, pollutants generated largely by traffic, industry, and wildfires. Adolescents exposed to higher levels of these contaminants showed accelerated thinning of the cerebral cortex, particularly in frontal and temporal regions responsible for executive function, emotional regulation, and social cognition. Cortical thinning is a normal feature of adolescence, reflecting synaptic pruning and increasing neural efficiency. What concerns the authors is not thinning per se, but a shift in its pace and regional pattern.

Importantly, these associations emerged at pollution levels widely regarded as ordinary. This is not a story of extreme toxicity but of cumulative exposure shaping development subtly and unevenly. Ozone, by contrast, showed little relationship to cortical change, underscoring that not all pollutants act on the brain in the same way.

The study reinforces a broader truth often resisted in policy debates: neurological development is not governed by biology alone. It is embedded in environments shaped by infrastructure, regulation, and collective choices. Air quality, like education or nutrition, quietly enters the architecture of the developing mind.

Below are four more remarkable articles I found this week: (1) couples in arranged marriages report the same levels of romantic love as couples who chose their spouse; (2) depression is associated with physiological damage to the heart; (3) exposing children to screens before age two is linked to long-term changes in brain development and higher anxiety in adolescence (PARENTS, PLEASE!!!! My goodness!); and (4) when teenagers exercise together, they are more likely to persist in maintaining healthy exercise habits.